Partial Orders: Part 1

Order is such a basic concept in programming that i don’t think about it often. I associate ordering with sorting, and sorting usually does what i expect:

λ> import Data.List

λ> let x = [4,1,2,5,3]

λ> sort x

[1,2,3,4,5]

λ>The sorted list is ordered, but the original list x is also ordered (ie, it has a first element, a second, etc.). In fact, order is part of what distinguishes a list from, say, a set or a map. Even if one of those latter data structures has elements that can be ordered, i don’t expect that i can ask for an element by position as i would with a list:

λ> x !! 3

5So informally we have two ideas of order: one that has to do with the natural way that we sort items, and another that has to do with being able to give items a position (or, an ordinal)

More formally we can describe order as a binary relation. At the most basic level a relation R connects items in a set (or two sets), so

means a is related to b. A relation could just be a set of tuples, but usually we think of it as an operator. For the purpose of order we want a relation that is:

- Reflexive: \( a \ R \ a \)

- Transitive: If \( a \ R \ b \) and \( b \ R \ c \) then \( a \ R \ c \)

- Antisymmetric: If \( a \ R \ b \) and \( b \ R \ a \) then \( a = b \)

And usually we want the relation to be total, meaning that for any a,b in the set(s) of interest either \( a \ R \ b \) or \(b \ R \ a\).

For our list above we can see that \(\leq\) is a relation that will work (or \(\geq\)). One reason I chose Haskell for these examples is that it’s explicit about order. Looking at the \(\leq\) in the repl we see:

λ> :i (<=)

class Eq a => Ord a where

...

(<=) :: a -> a -> Bool

...

-- Defined in ‘ghc-prim-0.4.0.0:GHC.Classes’

infix 4 <=Basically this tells us that the \(\leq\) operator requires operands of the class Ord, which is a subcass of Eq

λ> :i Eq

class Eq a where

(==) :: a -> a -> Bool

(/=) :: a -> a -> BoolIf we look closely at the Ord type class, we can see that it not only defines several operators for comparison but that there are instances of many types that we’d expect to be able to compare, including of course the Int type i used in the list above:

λ> :i Ord

class Eq a => Ord a where

compare :: a -> a -> Ordering

(<) :: a -> a -> Bool

(<=) :: a -> a -> Bool

(>) :: a -> a -> Bool

(>=) :: a -> a -> Bool

max :: a -> a -> a

min :: a -> a -> a

-- Defined in ‘ghc-prim-0.4.0.0:GHC.Classes’

instance (Ord a, Ord b) => Ord (Either a b)

-- Defined in ‘Data.Either’

instance (Ord k, Ord v) => Ord (M.Map k v)

...

instance Ord Int -- Defined in ‘ghc-prim-0.4.0.0:GHC.Classes’

instance Ord Float -- Defined in ‘ghc-prim-0.4.0.0:GHC.Classes’

instance Ord Double -- Defined in ‘ghc-prim-0.4.0.0:GHC.Classes’

instance Ord Char -- Defined in ‘ghc-prim-0.4.0.0:GHC.Classes’

instance Ord Bool -- Defined in ‘ghc-prim-0.4.0.0:GHC.Classes’

...The two familiar operations that require comparisons on totally ordered sets are sorting and selection (ie, finding the k_th smallest element in a set). Algorithms for these are among the most fundamental and well-understood in computer science.

But suppose that the total criterion is removed from our defintion of a total order. In other words, there are now elements (a,b) in the set where neither \( a \ R \ b \) nor \( b \ R \ a \); or even more simply a and b can’t be compared. An example of such a set would be the set of applicants to a university. You can compare physics applicants to other physics applicants, and political science applicants to other political science applicants; but the departments might have no basis for comparing applicants across departments. Another example from computer science is the happened-before relation from concurrent computing. If operation e1 happened-before e2 then at least in a logical sense e1 must complete before e2 can start. However, there might also be events e2 and e3 that can happen concurrently and so we can’t say anything about which starts or finishes first. They can’t be compared with happened-before and so they can’t ordered linearly in time.

This type of set and the operation that compares comparable elements (P, \(\leq\)) is called a partially ordered set or poset. Most of what follows here is inspired by the paper Sorting and Selection in Posets by Daskalakis, Karp, et.al (i’m using this arXiv preprint:, but the full paper was published in SIAM Journal of Computing). That paper presents several algorithms related to sorting posets, but here i’m working up to the basic parts; specifically the idea of a chain decomposition of a poset, and a data structure they describe called ChainMerge.

First, what exactly does it mean to sort a poset? You can see that within a partially ordered set there are subsets that are totally ordered (eg, the political science students). So one view of sorting a poset is to find the smallest number of subsets that can be totally ordered. Another view is that the purpose of sorting in both total and partial orders is to create a datastructure that makes comparisons of elements simple, ie O(1). I first got the idea for looking at this topic from Lance Fortnow’s blog, and he states it this way:

Given a set A of n elements from a totally ordered set come up with a data structure of size O(n) such that the operation Given \( x,y \in A \)which one is bigger? can be done in O(1) time. While setting up the data structure you would like to to do this with as few comparisons as possible. We will assume that comparing two elements of {1,…,n} is easy.

The latter is what the ChainMerge structure does in the Daskalakis paper. Note also that determining the partial order is equivalent to constructing a directed graph of the elements, which i’ll show in more detail below. This might make you think of topological sorting, which is related but not quite the same.

First, some definitions: a chain is a set of mutually comparable elements in a poset. A chain decomposition is a set of disjoint chains that when unioned give the whole poset. An anti-chain is a set of non-comparable elements. The width of a poset (w(P)) is the maximum cardinality of an anti-chain.

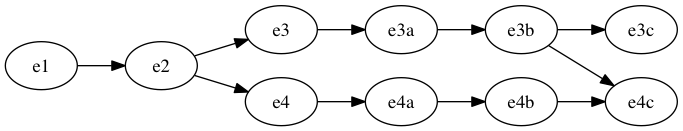

The ideas of a chain and a chain decomposition seemed fairly clear to me, althought it might not be immediately obvious that there can be more than one decomposition. However, the anti-chain idea took me a while to grasp, so i’m going to present an example that i hope will help explain. Going back to the happens-before relation, imagine the following set of events, which i’ll show as a directed graph

There are numerous ways this set could be decomposed into chains since any path along the digraph is a chain. It might be less clear how to construct anti-chains. From the graph and the way the happened-before relation is constructed, it’s fairly obvious that items e3 and e4 are not comparable (they can happen concurrently, or it doesn’t matter in which order they happen). Are there other elements we can add to this anti-chain? Actually, no. The elements e1 and e2 are clearly comparable to both, and any of the elements after these elements are comparable to at least one or the other. There are numerous other sets of 2 elements we could choose for anti-chains: (e3a, e4a), (e3a, e4b), (e3c, e4c), but none larger than 2. Since the largest anti-chain that we can make has two elements, this poset has a width of two.

Although there are several chain decompositions, what we want is a decomposition that is the same size as the width of the poset. This decomposition can be found in the general case using an algorithm for maximal bipartite graph matching (like the Hopcroft-Karp algorithm, yes, the same Karp as the poset paper referenced above). Basically you duplicate all of the elements of the set on each side of a bipartite graph and make an edge between the elements that can be compared. The maximal matching is the set of edges that match the most pairs without any edge sharing a vertex. There are a couple of options in our example depending on whether we associate the first two elements with the upper branch or the lower. Note also that there is guaranteed to be a decomposition of the same size as the width of P according to Dilworths’s theorem.

Once we have the ability to construct a chain decomposition like this, we can create the ChainMerge data structure described in the Daskalakis paper. However, their description of building ChainMerge uses an oracle that tells you either how two elements are related or that they are not comparable. This allows them to separate the complexity of sorting and selection from the complexity of individual comparisons. Here our oracle will simply be a comparison function implemented for a given type. For an example of a partially ordered set, I’m going to use a set of the subsets of a larger set, specifically a randomly chosen list of subsets from the sequence of integers [1..10]. The partial order relationship in this case is \( \subset \), so A is less than B if it is a subset. Obviously in some cases there will be pairs in this set where neither is a subset of the other and so are incomparable.

To implement an “oracle” we’ll use the PartialOrd type class from Haskell’s logfloat package. I like this implementation because it has a PartialOrd type class that parallels the regular Ord class, but the comparison function (cmp here rather than compare) returns Maybe Ordering so that Nothing can be used to indicate incomparable elements.

data Ordering = LT | EQ | GT

class PartialOrd a where

-- | like 'compare'

cmp :: a -> a -> Maybe OrderingSo to get a comparison function we need to implement the PartialOrd class for a set of Integers.

import qualified Data.Set as Set

import Data.Number.PartialOrd

newtype IntSet = IntSet (Set.Set Int) deriving(Show)

toIntSet :: Set.Set Int -> IntSet

toIntSet s = IntSet s

fromIntSet :: IntSet -> Set.Set Int

fromIntSet (IntSet s) = s

instance PartialOrd IntSet where

cmp x y | Set.isSubsetOf (fromIntSet x) (fromIntSet y) = Just LT

| Set.isSubsetOf (fromIntSet y) (fromIntSet x) = Just GT

| (fromIntSet y) == (fromIntSet x) = Just EQ

| otherwise = NothingNow we’ve got all the pieces we need to compare the elements of our set:

let s1 = toIntSet $ Set.fromList [1,2,3]

let s2 = toIntSet $ Set.fromList [2,3]

let s3 = toIntSet $ Set.fromList [4,5]

cmp s1 s2

Just GT

cmp s2 s1

Just LT

cmp s1 s3

NothingNow we can start looking at the steps in building ChainMerge, which will be the subject of Part II.